The Baku COP29 ended with a fizz, with the advanced industrial countries pledging to contribute $300 billion per year by 2035 to help Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs) to cope with the impact of climate change. This pledge represents progress over the previous Paris Agreement one for $100 billion per year, but remains to be tested, is far short from the $1.3 trillion/year considered to be needed to meet this existential challenge. However, even this truncated pledge was clouded by a controversial inclusion of monies from private sector and larger emerging markets, as well as from oil producing countries.

The impact of climate change is particularly dire for the low-income/highly indebted countries. The risks range from potential physical disappearance for low-lying island countries of the Indian Ocean and Pacific oceans to destruction caused by increasingly deadly natural disasters and droughts. This category of countries has historically contributed very little to global warming, but is paying a disproportional price in terms of its impact. At the same time, high levels of indebtedness, little fiscal space, weak governance and inadequate infrastructure make them more vulnerable to climate change’s effects. Coping with the impact of climate change requires action on two fronts: building resilience and promoting adaptation.

Building resilience includes two components. First, providing funds and building institutions to help the countries to mitigate the economic and social impact of droughts, floods and other natural disasters. Second, to upgrade infrastructure—energy, water management, communications, etc..) to mitigate the impact of climate change—such as flood prevention, water resources management, improved roads, emergency stockpile management, etc.. Adaptation requires helping the countries in the transition to renewable energy, investing in more resilient critical infrastructure, and strengthening the institutional framework.

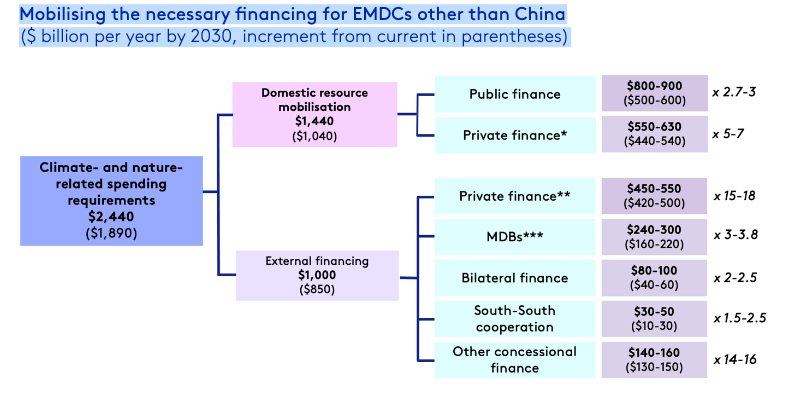

A recent study on the financial needs of EMDEs1 (estimate that they will need $2.5 trillion/year by 2030 and $3.5 trillion a year by 2035 in investments to deal with climate change. Clearly, public bilateral and multilateral funds must represent seed money to promote private sector investments, with public monies becoming a risk management backstop.

The COP29 Summit, paradoxically held in the petro-state Azerbaijan, clearly came short in both financial and policy commitments, leaving out the discussion of key questions. First, some of the largest emerging markets (China, India, and Brazil) are themselves major polluters and contributors to global warming. Yet, they are not explicitly committed to contribute to funding initiatives to assist the low-income countries. The same reasoning applies to the major oil-producing nations, whose massive assets can be a powerful source of funds. Second, the COP framework has not resolved the tension between the continued global reliance on hydrocarbons and the need to transition to renewable energy. In this regard, the main oil producing countries have managed to obscure the debate, and the upcoming climate change-denying Trump administration is unlikely to be helpful in this regard.

Despite its shortcomings, COP29 managed to keep the issue of climate change on the front burner, and incremental change is better than no progress. For the EMDEs and the world, dealing with climate change is at the center of both macroeconomic and microeconomic concerns. In this context, the multilateral financial institutions are playing a critical role, providing financial resources, technical assistance and coordination of multilateral and bilateral initiatives2. Continued coordination of public investments and public/private initiatives will be key to further progress in this regard.i.

"Third Report of Independent High-Level Experts on Climate Finance: Raising Ambitions and Accelerating Delivery of Climate Finance, November 2024

https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Raising-ambition-and-accelerating-delivery-of-climate-finance_Third-IHLEG-report.pdf)

The IMF and the World Bank play a key role in coordinating official monies. The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust has so far issued a total of $9.5 billion in funds